Project Apollo might have been commissioned as a feel good project to boost the morale of a bruised superpower, but it was conceived as a piece of pure scientific exploration.

In his final essay marking the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11 - which launched on 16 July 1969 - Dr Christopher Riley looks back at the part scientific curiosity played in inspiring the Moon landings.

One of Arthur C Clarke's "laws" states that "any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic".

Some technological advancement take place over centuries, and some can occur within a single generation - leaving those who lived through it with that feeling of magic.

Apollo was an even faster example. Within eight years, we leapt from being unable to fly in space to living briefly on the Moon.

The world's oldest man at the time - Charlie Smith - reportedly born in 1842 was at the launch of the final Moonshot and simply couldn't believe where the men onboard were heading.

| The science imperative was there |

Even Apollo 11's Michael Collins, a man intimately connected with the machinations of his mission, once said he felt that there was some magic within the smooth clockwork-like running of his flight.

Such technological leaps require springboards of scientific curiosity, and Apollo was no exception.

Unsure about where the new president would point them (as Nasa always tends to be when new administrations come to office), the agency had prepared a number of options for President Kennedy to consider.

Chief amongst these were plans for a manned lunar exploration programme; conceived not by military strategists for reasons of Cold War bravado, nor by politicians with an eye on national prestige, but by one of the greatest scientific minds of the 20th Century - a man passionately interested in our origins.

Planetary scientist Harold Urey had first suggested to Nasa that it commence a lunar exploration programme in the 1950s.

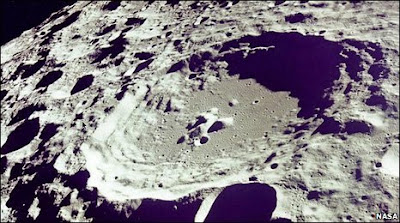

Urey figured that the Moon, lacking atmospheric weathering and the recycling of its crust through plate tectonics, might preserve some truly ancient geological relics from the early Solar System, long gone on Earth.

Ignited by Urey's curiosity, Nasa came up with ambitious plans to investigate his theories, harnessing an armada of robotic mapping missions and culminating in a manned landing.

With an estimated price tag of $11bn, there was little chance of it being adopted by the new President, but Nasa had it on the table just in case.

That case arose on the 12 April 1961, just three months after Kennedy had come to office, when Major Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the Earth.

Kennedy immediately consulted his Vice President to find out what they could do to restore some national pride and Johnson was quick to recommend Nasa's novel lunar exploration programme.

At first Kennedy was reportedly unsure. With no guarantees of success, it seemed like a lot of money to convince Congress to spend. But Johnson was persuasive.

| The Saturn V astonished all those who saw it, and felt its power |

"To be second in space is to be second in everything," he told the President. Put that way, Kennedy had little choice but to embrace it.

Marshalling over 400,000 men and woman across America for this single, focused and determined goal, Nasa's philosophy borrowed from another of Clarke's laws - "the only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible".

Examine the newspapers from any time during the 1960s and you will read of Apollo's "show stopping" engineering set-backs.

From the seemingly insurmountable problems of getting each stage of the Saturn V to work, to the challenges of making the Command Module safe following the fire that killed the first Apollo astronauts, even the engineers would have told you at times that they didn't think it could be done.

But against all the odds, on the 16 July 1969, just 30 months after the fatal fire - the first Saturn V rocket attempting to carry men from the surface of one world to another rose into the Florida sky.

Those who had worked on Apollo - who intimately knew every nut and bolt - were left gasping at what they'd accomplished.

For the rest of us - marvelling at the heaviest vehicle ever to lift off the ground - it was nothing short of magic.

Three days later when the first men to reach another world arrived, their initial act, within moments of setting foot there, was to document and collect a precious sample of lunar dust, to share with laboratories across the Earth.

It was a fitting thing to do at the climax of a voyage which had been started by a grand scientific idea about our origins.

As this series of essays has shown - whilst Apollo emerged during troubled times; accelerated into being as an antidote to the persistent terror of Armageddon, what transpired was far more than a Cold War race.

America's immense national effort devoted to something other than war had united the world in admiration.

In these similar times of great uncertainty - engaged in more un-winnable wars and threatened by new terrors - perhaps we need another magical project inspired by scientific curiosity and delivered by engineering ingenuity to lift our spirits and win over hearts and minds.

The writer J. Bainbridge summed up Apollo as "a story of engineers who tried to reach the heavens".

Is it time once more to challenge our scientists and engineers to reach for the heavens for the sake of all mankind?

News updated bye BBC

No comments:

Post a Comment